त्रुटि को ठीक करें "साइटमैप देखा नहीं जा सका"

Google Search Console त्रुटियों से जूझना बंद करें। अपने साइटमैप को सही तरीके से अनुक्रमित करें और अपने जैविक ट्रैफ़िक की वृद्धि देखें।

IndexJump मुफ्त आज़माएं

Google Search Console त्रुटियों से जूझना बंद करें। अपने साइटमैप को सही तरीके से अनुक्रमित करें और अपने जैविक ट्रैफ़िक की वृद्धि देखें।

IndexJump मुफ्त आज़माएं

साइटमैप और अनुक्रमण समस्याओं को हल करने में हमारी विशेषज्ञता की खोज करें

When a sitemap cannot be read by search engines, it interrupts a vital communication channel between your Shopify store and the crawlers that index its pages. For ecommerce sites, this gap can translate into slower discovery of new products, updates to inventory, and changes in pricing or promotions. In practice, an unreadable sitemap can lead to delayed indexing, missed opportunities for product visibility, and a fragmented crawl of your catalog. While Shopify inherently manages many technical duties, the sitemap is still a critical artifact that informs search engines about which pages to prioritize and how often they should revisit them, especially for large catalogs with frequent updates.

The impact on visibility is not merely theoretical. Search engines rely on sitemaps to understand site structure, confirm canonical versions of pages, and detect changes in content. When Shopify users encounter sitemap read failures, search engines may fall back to discovering pages through internal linking or external signals, which can be slower or less reliable. For merchants running promotions, seasonal launches, or inventory flushes, even a short window of unreadable sitemap can delay indexing of new or updated URLs, reducing the chance that customers see those changes in search results promptly.

From a crawl-efficiency perspective, an unreadable sitemap places more burden on the crawl budget. If search engines struggle to parse the sitemap, they may deprioritize or skip certain sections of the catalog, particularly category pages or new product entries. This behavior is especially consequential for stores with hundreds or thousands of SKUs, where timely indexing of updates is essential to sustaining organic traffic and conversion rates. The practical takeaway for Shopify store owners is clear: ensuring a readable sitemap is an investment in reliable content discoverability and consistent organic performance.

For merchants who rely on Shopify as a performance lever, the sitemap is part of a broader SEO system. It complements internal linking, product schema, and structured data signals. When the sitemap reads correctly, it helps engines map product pages, collections, blog content, and policy pages into a coherent index, supporting more efficient crawls and timely indexing. Conversely, unreadable sitemaps can create blind spots in the index, making it harder for potential customers to locate product listings, filter results, or access new content. This dynamic is particularly critical for stores with rapid inventory changes or frequent price adjustments, where accuracy and timeliness in indexing correlate with revenue opportunities.

From a user-experience viewpoint, an readable sitemap often correlates with better site health signals. While users do not directly interact with a sitemap, the underlying indexing health influences how quickly product pages appear in search results and how accurately rich results (like product snippets) can be shown. In short, a readable sitemap supports both discovery and trust: it helps search engines surface the most relevant and up-to-date content to shoppers while reinforcing the perceived reliability of the storefront.

Key considerations for Shopify merchants include understanding how sitemap issues arise, recognizing the signs of a problem, and preparing a workflow for quick remediation. This multi-part guide walks through practical steps that align with industry best practices and platform-specific nuances, including how to verify the sitemap URL, test accessibility, validate XML, and ensure that crawlers can reach the file without hindrance. The objective is to establish a repeatable process that minimizes downtime, keeps indexing aligned with product updates, and preserves overall search visibility.

As you progress through this series, you’ll gain a practical framework for diagnosing unreadable sitemap scenarios, adjusting your Shopify configurations, and safeguarding ongoing visibility. For broader context on how search engines handle sitemaps and the recommended practices, refer to established guidelines from authoritative sources such as Google’s sitemap guidelines.

The following sections of this guide will zoom in on practical actions you can take if you encounter a sitemap that cannot be read. While the problem can stem from several root causes, a disciplined verification approach helps you isolate the issue quickly and apply the right fix without disrupting live commerce. The early part of this article sets the expectations: you will learn how to locate the official sitemap, assess accessibility, validate structure, and prepare for re-submission to search engines once the file is readable again.

In Shopify environments, several common scenarios can trigger unreadable sitemap states. These include misconfigured robots.txt rules that inadvertently block the sitemap URL, temporary hosting issues, or runtime errors in dynamic sitemap generation during heavy traffic. While these situations are often resolvable with targeted adjustments, they still warrant a structured diagnostic approach to prevent recurrence. The rest of Part 1 outlines the conceptual impact, while Part 2 will guide you through locating and verifying the sitemap URL within Shopify’s settings, ensuring you reference the correct path for crawling and submission.

Understanding the broader ecosystem helps you contextualize the problem. Sitemaps are not isolated artifacts; they are part of a coordinated SEO strategy that includes robots exclusions, canonical signals, and server configurations. Ensuring their readability is not only about fixing a file but also about preserving the integrity of how your store communicates with search engines. This approach reduces the risk of indexing gaps during campaigns, launches, or inventory restructures. In Part 2, you’ll learn how to locate the sitemap URL within Shopify, verify you’re referencing the correct path, and begin the process of testing access — the first concrete steps toward remediation.

Building on Part 1’s emphasis on a readable sitemap, the next practical step is identifying the exact sitemap location you should reference for crawling and submission. For Shopify stores, the canonical sitemap is hosted at a predictable path, but validation requires confirming the correct domain and URL variant in use. Begin with a concise verification process that centers on the primary domain customers see and the version used by search engines. This ensures you’re not chasing a stale or blocked sitemap URL that could contribute to the error message about a sitemap that could not be read.

The official sitemap location is usually exposed as a /sitemap.xml resource on the primary domain. In many Shopify setups, you may encounter two plausible paths:

To determine which variant search engines expect, check the site’s robots.txt, which commonly includes a line like "Sitemap: https://yourdomain.com/sitemap.xml". If the robots.txt points to a different host or path, align your submission with that directive. You can inspect robots.txt directly by visiting https://yourdomain.com/robots.txt. If you manage multiple domains or redirects, confirm that the canonical sitemap is the one available on the primary domain used for indexing. For authoritative guidance on sitemap structure and submission, refer to Google's sitemap guidelines.

Once you identify the likely sitemap URL, perform a quick accessibility check in a browser or via a lightweight HTTP request. A successful discovery is a 200 OK response with a content type suitable for XML, typically text/xml or application/xml. If you encounter redirects, 404s, or 403s, you’re observing the same access symptoms that can cause a sitemap read failure. Documenting the exact URL variant that returns a readable response helps your remediation workflow stay aligned across teams and tools.

In Shopify environments, a frequent signal of correctness is the presence of a sitemap index at /sitemap.xml that links to sub-sitemaps for products, collections, pages, and blog posts. This hierarchical structure is normal and expected; it enables search engines to crawl large catalogs efficiently. If your sitemap.xml resolves but the content appears incomplete or missing expected sections, move to the next verification steps to confirm the integrity of the underlying files and their access rights.

Attach a simple checklist to your process for sustaining this step over time. Record the confirmed sitemap URL, the domain variant used for indexing, and the timestamp of the last test. If you rely on a content delivery network (CDN) or caching layer, note any recent changes that could affect availability. This disciplined documentation helps prevent future occurrences of the same unreadable sitemap scenario and supports faster re-indexing after fixes. For teams seeking continuous improvements, our SEO Services can help establish automated health checks and alerting for sitemap health on Shopify stores.

In cases where the sitemap URL is not easily reachable from hosting infrastructure, or if the store uses a dynamic generation path that occasionally alters the URL, plan a fallback approach. Maintain a canonical reference in your internal SOPs and ensure that any app or theme changes do not unintentionally block sitemap access. After confirming the sitemap URL, the natural next step is to verify accessibility and HTTP status in a structured way, which Part 3 will cover in detail. This ensures you’re not only finding the right file but also ensuring it is reliably readable by crawlers.

After you locate the sitemap URL, the next crucial step is to verify accessibility at the server level. Start with a straightforward check using a browser or a lightweight HTTP header request to determine the status code returned by the sitemap URL. A clean read typically surfaces a 200 OK with an XML content type. If you encounter redirects, 403, 404, or 500-series errors, you’ve identified the layer responsible for the unreadable sitemap and can target remediation accordingly.

To perform a more repeatable test, use a header-only request that fetches only the status line. For example, a curl command such as curl -I 'https://yourdomain.com/sitemap.xml' or curl -I 'https://yourdomain.com/sitemap.xml' -L can reveal whether the sitemap is reachable and if redirects are involved. If the final URL after redirects is a different host or path, ensure that this final URL matches what search engines are supposed to crawl for indexing. Consistency between the URL you submit and the URL your robots.txt and Google Search Console expect is essential to avoid confusion for crawlers.

Redirects warrant special attention. A chain of redirects can cause crawl inefficiencies or timeouts, especially for large catalogs where the sitemap is referenced by multiple signals. If you observe a 301/302 redirect, verify that the destination URL remains under the same primary domain and uses the same protocol (https). A mismatch in protocol or cross-domain redirects may confuse crawlers and hinder timely indexing. If redirects are necessary due to domain changes or CDN routing, update your robots.txt and sitemap references to reflect the canonical path that you want crawlers to use.

In cases where the server responds with 403 Forbidden, 404 Not Found, or 500 Internal Server Error, you must diagnose permission and server health issues. A 403 can indicate IP-based access controls, user-agent restrictions, or misconfigured security rules that block crawlers. A 404 suggests the sitemap was moved or removed without updating the public references. A 500-level error signals a transient server problem or misconfiguration on the hosting stack. Record the exact status code, the time, and any recent changes to hosting, edge caching, or security plugins so you can reproduce and verify fixes later.

Caching layers and content delivery networks can mask underlying accessibility problems. A user might still receive a cached 200 response even if the origin server is returning errors. To avoid this, purge relevant cache layers after making changes to the sitemap path or server configuration, and re-test directly against the origin URL. If you rely on a CDN, ensure the origin pull path aligns with the URL you intend search engines to crawl. This practice helps prevent stale or blocked sitemap responses from misleading crawlers.

Another layer to consider is how the sitemap is served in relation to robots.txt. If robots.txt blocks the sitemap URL, search engines will not fetch it even if the URL is technically reachable. Confirm that the robots.txt file located on your domain does not disallow the sitemap path and that there is a clear directive like Sitemap: https://yourdomain.com/sitemap.xml unless you have a platform-specific reason to manage the path differently. If you find such blocks, work with your hosting or platform provider to align robots rules with the intended crawl strategy.

As you verify accessibility, document each result with timestamped notes and corresponding URL variants. This creates a traceable remediation trail, making it easier to coordinate with developers, your SEO team, or an agency. For ongoing prevention, consider implementing automated health checks that periodically validate the sitemap URL, status codes, and content-type. Our team offers automated monitoring as part of our SEO services, which can be integrated with Shopify-specific configurations for quicker detection and response, see SEO Services.

In Part 4, you’ll translate these accessibility findings into concrete validation steps for the XML structure, ensuring the sitemap’s syntax and content align with best practices. Google’s guidelines remain a reliable reference point for structure and submission expectations, available here: Google's sitemap guidelines.

Key practical takeaways from this section include: verify a clean 200 response or acceptable redirects, identify and fix blocking or misrouting through server and CDN configurations, and ensure robots.txt aligns with the sitemap URL you intend to expose to crawlers. By maintaining consistent URL references and robust access tests, you reduce the risk of sitemap readability failures that could similarly affect Shopify stores with sizable inventories and frequent updates.

XML validity is the backbone of a readable sitemap. For Shopify stores, even small syntax errors can render the entire sitemap unreadable by crawlers, triggering the frustration around a sitemap could not be read and delaying indexing of newly added products, collections, or content. A disciplined validation process not only catches mistakes early but also strengthens long-term crawl reliability. This section translates the theory of a readable sitemap into concrete, platform-aware actions you can implement with confidence.

Begin with the fundamentals of XML syntax. Ensure every tag is properly opened and closed, attributes use consistent quotation marks, and there are no stray characters outside the XML declaration. A well-formed sitemap starts with an XML declaration such as <?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?> and follows the hierarchical rules of the Sitemap Protocol. Even seemingly tiny errors, like missing end tags or an unescaped ampersand, can invalidate parsing by search engines and trigger read failures.

To operationalize this, employ an XML validator as part of your workflow. Copy the sitemap content into a validator tool and review the reported issues. Focus first on structural problems: unbalanced elements, incorrect nesting, and syntax that violates XML rules. After resolving these, re-validate to confirm that the file is now well-formed. This step is essential before you assess encoding and content accuracy, because a syntactically invalid file cannot be parsed by the engine even if the data appears correct at a glance.

Beyond well-formed XML, encoding consistency matters. UTF-8 is the industry standard for sitemaps and ensures compatibility with the broadest range of crawlers and content characters. If your store uses non-ASCII characters (for example in product names or URLs), confirm that the encoding declaration matches the actual file encoding and avoid mixed encodings within the same sitemap. Mismatches often surface as garbled characters or parsing errors in certain sections, which can cause partial indexing failures even when most of the sitemap is correct.

Next, validate the structural conventions of the Sitemap Protocol. Shopify sitemaps typically use a sitemapindex that links to sub-sitemaps for products, collections, pages, and blog posts. Each entry must include a <loc> tag with a fully qualified URL and, optionally, a <lastmod> tag formatted in ISO 8601. Validate that each URL uses the same canonical domain and protocol and that there are no trailing spaces or line breaks within tags. Inconsistent URL schemes or mismatched domains can confuse crawlers and lead to incomplete indexing even when the XML is otherwise valid.

A practical approach is to run a targeted validation pass on a sample subset of URLs before validating the entire file. This helps you identify domain or path-level issues that could cause broader reading problems. For Shopify stores with large catalogs, ensure that dynamic URL generation does not introduce malformed slugs or spaces that would render a URL invalid. If you maintain multiple sub-sitemaps, confirm that the linking structure in the sitemapindex is accurate and that no orphaned entries exist that point to non-existent resources.

Additionally, watch for encoding anomalies in the URL values themselves. Special characters should be percent-encoded where required, and you should avoid raw characters that break XML parsing. A clean, consistent encoding policy reduces the risk of misinterpretation by search engines during crawl operations.

After achieving a clean, well-formed XML file, proceed to content validation. Confirm that all listed URLs are live, accessible, and on the correct domain with the expected protocol. This ensures there is no mismatch between what the sitemap declares and what search engines fetch. If you use a staging domain or alternate versions for testing, clearly separate those from your production sitemap to prevent accidental indexing of test content.

To support ongoing quality, couple XML validation with automated health checks. A periodic pass that validates syntax, encoding, and structural conformance helps catch regressions caused by theme updates, app integrations, or CDN reconfigurations. If you would like expert assistance in maintaining a robust sitemap workflow within Shopify, our SEO Services can tailor automated validation and alerting to your store scale and update cadence.

Key actions to take from this part stop include:

For additional context on how search engines interpret and validate sitemaps, refer to Google's official guidelines at Google's sitemap guidelines. This ensures your Shopify sitemap aligns with the broader standards used by major search engines and reduces the risk of misinterpretation during indexing.

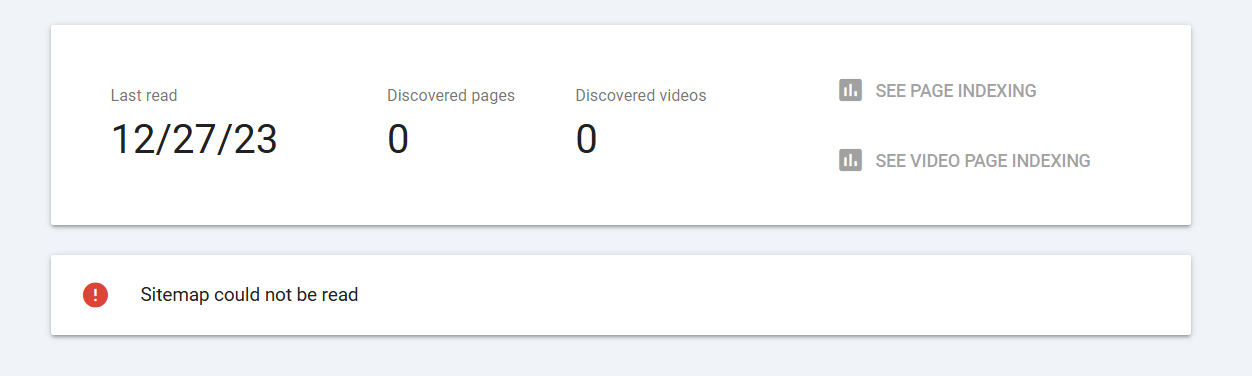

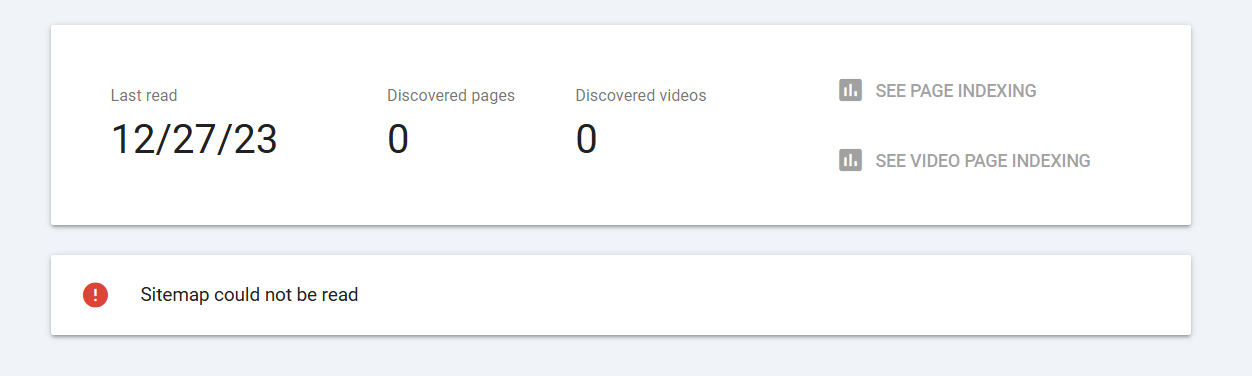

A sitemap is a structured map of a website’s pages that helps search engines discover and crawl content more efficiently. When Google Search Console reports that a sitemap could not be read, it signals a barrier to how Google discovers new or updated URLs under that property. This situation does not automatically mean your site is invisible to search engines, but it does raise the risk that newly published or reorganized pages may not be discovered promptly through the sitemap pathway. Understanding the nuance between a read failure and broader crawl issues is essential for diagnosing the root cause and restoring optimal indexing velocity.

In practice, you might see a message in Google Search Console such as "Sitemap could not be read." This could appear for a single sitemap file or multiple files, and it often correlates with technical problems that prevent Google from retrieving or parsing the file correctly. The immediate business impact is usually a slower or reduced visibility of newly added content through the sitemap, especially for sites that rely heavily on structured URL publication for priority indexing.

From an SEO perspective, the consequence depends on how robust your crawl signals are beyond the sitemap. If your site is otherwise easy to crawl (well-structured internal links, clean robots.txt, solid canonical practices) and Google discovers new pages via links, the impact may be limited. Conversely, for large catalogs of content added regularly via a sitemap, read failures can bottleneck indexing. It is prudent to treat a sitemap read failure as a signal to perform targeted troubleshooting rather than assuming a full indexing halt.

When a sitemap cannot be read, the Search Console interface typically surfaces several indicators that help you triage the issue. Pay attention to the following signals:

For authoritative guidance on the expected format and behavior of sitemaps, refer to Google's sitemap overview and the official Sitemap Protocol. These resources explain how Google parses sitemaps, common pitfalls, and recommended validation steps. Pairing these external references with in-house checks strengthens your debugging process and demonstrates best-practice adoption in your SEO playbook.

In addition to Google’s documentation, reviewing the sitemap protocol and validators (such as those provided by the Wikimedia or sitemaps.org ecosystems) can help you distinguish syntactic issues from host/configuration problems. The goal is to confirm that the sitemap is both accessible and well-formed before diving into deeper server or hosting configurations.

From a workflow perspective, treating the issue as a multi-layered problem accelerates resolution. Begin with quick accessibility checks, then validate the XML, verify host alignment, and finally inspect server responses and caching policies. This approach minimizes guesswork and creates a reproducible diagnostic path you can document for future maintenance.

Part 1 of this 12-part series establishes the conceptual framework for diagnosing a sitemap read failure. The subsequent parts will guide you through concrete, repeatable steps: verifying accessibility, validating syntax, ensuring host consistency, checking HTTP responses, identifying blocking rules, and implementing durable fixes. If you want to explore practical steps immediately, you can explore related checks in our broader services section or read practical guides in our blog.

Although this is an overview, you can start with a concise triage checklist that mirrors the logic of the deeper checks in later parts. First, copy the sitemap URL from Google Search Console and fetch it in a browser or a simple HTTP client to confirm it returns HTTP 200. If you receive a 403, 404, or 5xx, you know the problem lies beyond Google’s reach and within server or access controls. Second, ensure the sitemap is hosted on the same domain and protocol as the site property in Search Console. A host mismatch is a frequent cause of read failures. Third, validate that the sitemap is properly encoded in UTF-8 and adheres to the sitemap protocol (XML well-formed, proper closing tags, and correct URL entries).

Finally, remember that some environments employ security layers like firewalls, IP whitelists, or authentication barriers that can temporarily block automated retrieval of the sitemap. If you encounter persistent access issues, these components are among the first things to inspect. The next sections of this guide will walk you through each of these checks in a structured, repeatable way, so you can restore sitemap reliability with minimal downtime.

For continued reading, see Part 2, which dives into verifying basic accessibility and URL availability, including how to interpret HTTP status codes and content types. This progression ensures you have a solid, practical foundation before moving to more advanced validation and remediation steps.

As you advance through the series, you’ll develop a repeatable process you can apply to other properties and clients, reinforcing confidence that sitemap-related issues do not derail overall indexing momentum. The practical payoff is measurable: faster recovery times, more predictable indexing, and clearer communication with stakeholders about SEO health and resource allocation.

After confirming that a sitemap read failure is not a general crawl issue, the next critical step is to verify basic accessibility and URL availability. This phase focuses on whether Google can actually reach the sitemap file on your hosting environment, whether the domain and protocol match your Search Console property, and whether any simple access controls are inadvertently blocking retrieval. Getting these basics right often resolves read failures without complex remediation. For broader context, see Google's guidance on sitemap access and validation linked in the references at the end of this section.

When you start troubleshooting, keep the sitemap URL handy from Google Search Console. Your first moves are to confirm that the URL responds with HTTP 200 and serves XML content encoded in UTF-8. If the URL redirects, you should understand where the final destination sits and ensure that the end result remains a valid sitemap file rather than a misconfigured page or a generic HTML error.

Practically, you can perform these checks using common tools. A curl command such as curl -I https://example.com/sitemap.xml will reveal the HTTP status, content-type, and cache headers. If you see a 301 or 302 redirect, repeat the request using curl -L -I to follow the redirect chain and confirm the final status and content. A 200 status with an XML content-type is typically the fastest green signal that the URL is accessible and properly served.

In addition to direct fetches, validate the host alignment by inspecting the property settings in Google Search Console. If your property is configured for https://www.yourdomain.com, ensure the sitemap URL is not a lingering variation such as http://yourdomain.com/sitemap.xml or https://yourdomain.com/sitemap.xml. These misalignments are a frequent cause of "sitemap could not be read" messages even when the file itself is correct.

Another practical consideration is the sitemap’s hosting path. While sitemaps can live in subdirectories, Google prefers consistency between the sitemap location and the site’s canonical host. If your site uses multiple subdomains or a dynamic routing setup, document where each sitemap lives and ensure that the URLs listed inside the sitemap remain on the same host and protocol. A mismatch here can trigger host consistency checks within Search Console and prevent successful reads.

Finally, review any security appliances that might intermittently block automated access to the sitemap. Firewalls, WAFs (Web Application Firewalls), or CDN rules may temporarily block requests from Google’s IP ranges. If you suspect this, temporarily whitelisting Google’s crawlers for the sitemap path or adjusting rate limits can restore normal access while you implement longer-term controls.

Accessible sitemaps provide a reliable signal to Google about which URLs to prioritize for indexing. When a sitemap is read successfully, Google can more quickly detect new or updated content, particularly for large catalogs or sites with frequently changing pages. Conversely, persistent accessibility issues can slow down indexing velocity, increase time-to-index for new content, and complicate data-driven decisions about content strategy. However, it’s important to balance this with the overall crawlability of the site; strong internal linking and clean URL structures can help Google discover content even if the sitemap has occasional read issues. For deeper guidance on how sitemaps complement other crawl signals, consult the official sitemap overview from Google and the Sitemap Protocol documentation referenced below.

As you proceed, keep a running record of the checks you perform, the outcomes, and any changes you implement. This habit not only speeds up remediation for future issues but also strengthens your team’s transparency with stakeholders about SEO health. If you’d like to explore related routines, our services section and our blog contain practical guides on crawl optimization and ongoing site health.

For reference, Google’s official sitemap guidance emphasizes both accessibility and correctness of the file’s structure. See the sitemap overview and the Sitemap Protocol for details on how Google parses and validates entries. Connecting these external references with your internal diagnostic process reinforces best practices and improves audit quality across projects.

In the next section, Part 3, you will learn how to validate the XML sitemap syntax and encoding to ensure the file is structurally sound and machine-readable, which is a natural progression after establishing reliable access.

Until then, adopt a disciplined triage workflow: verify accessibility, confirm host consistency, inspect redirects, and review security controls. This approach minimizes guesswork, accelerates restoration of sitemap reliability, and supports smoother indexing momentum across property changes. For ongoing reference, you can also review our practical steps in the related sections of our services or revisit insights in the blog.

XML syntax and encoding govern whether Google can parse a sitemap file at all. If the file is not well formed or encoded correctly, Google may ignore it, which can slow down indexing for newly published pages. Verifying syntax and encoding is the most deterministic step you can take before investigating hosting, access controls, or network-related blocks. This part focuses on ensuring the sitemap is structurally valid and machine-readable, so Google can interpret the listed URLs without ambiguity.

Start with the basics of XML correctness and encoding. A correctly formed sitemap uses the sitemap protocol, starts with a proper root element, and keeps each URL entry encapsulated within a

http://www.sitemaps.org/schemas/sitemap/0.9 so Google can recognize the file as a sitemap.& rather than a raw &.When you encounter a read failure, this set of checks helps isolate whether the problem lies in XML structure, encoding, or a misconfigured entry. If you find a malformed tag or an unescaped character, correct the XML, save with UTF-8 encoding, and re-upload the file for testing in Google Search Console. For a deeper understanding of the protocol itself, you can review the Sitemap Protocol documentation and validate against the official schema.

Encoding determines how non‑ASCII characters are represented and understood by crawlers. The sitemap should be encoded in UTF‑8, and you should avoid introducing a BOM that can disrupt initial parsing. Pay attention to how special characters appear in URLs and metadata, ensuring they are properly escaped or percent-encoded as required by the URL syntax.

& for ampersands, < for less-than, and > for greater-than where applicable.Useful validation steps include running the sitemap through an XML validator and a sitemap-specific checker to confirm both well-formedness and protocol compliance. For a practical workflow, pair these checks with a quick token test in your browser or a curl request to confirm the file is served with a 200 status and the correct content type.

For hands-on validation, consider tools such as online XML validators and the official sitemap validators. They help you confirm that the file adheres to the XML syntax rules and the Sitemap Protocol schema, reducing back-and-forth between teams and speeding up restoration of indexing momentum. You can also reference authoritative resources in our blog for practical validation patterns and common pitfalls.

Employ a mix of automated checks and manual review to ensure accuracy. Start with a quick syntax check using an XML validator, then perform a protocol-level validation against the sitemap schema. If possible, run a local test instance of the sitemap to confirm that each

After you complete these checks, you should be ready to re-submit the sitemap in Google Search Console. Monitor the crawler signals for improved read status and indexing activity. If issues persist, Part 4 will guide you through verifying the sitemap location, host consistency, and the hosting environment to eliminate server-side blockers. For broader site health insights, explore our services page or consult related guidance in our blog.

Once accessibility checks pass, the next critical axis is ensuring the sitemap XML is structurally sound and protocol-compliant. Read failures often originate from malformed XML or misapplied namespaces. A well-formed sitemap doesn't guarantee indexing speed, but it removes avoidable friction that slows discovery of new URLs.

At the core of the problem is adherence to the Sitemap Protocol. The protocol defines precise rules for the root element, namespaces, and the required loc field for each URL. Deviation in any of these areas can trigger Google to treat the sitemap as unreadable or invalid. The most common culprits are missing

urlset with the proper sitemap namespace: xmlns="http://www.sitemaps.org/schemas/sitemap/0.9". loc tag with an absolute URL starting with http or https. lastmod, changefreq, and priority should follow their definitions and use correct data formats. Beyond the basic rules, consider the distinction between a standard sitemap and a sitemap index. A standard sitemap contains multiple

Validation is the quickest way to diagnose these issues. Use an XML validator or the sitemap-specific validator to check for well-formedness and protocol compliance. If your validator flags a namespace mismatch, check that the root element includes xmlns with the exact URL above. If a

For external references and deeper validation techniques, see Google's sitemap protocol guidance and third-party validators. The combination of validated syntax and correct protocol usage dramatically reduces the likelihood of read failures, and it supports more efficient indexing by Google. In addition to the official resources, many SEO teams benefit from the practical insights shared in reputable industry blogs and documentation on best practices for sitemap maintenance.

To align with best practices, consider hosting strategies that ensure fast, reliable access to the sitemap. If you’re using a content delivery network (CDN) or a load balancer, verify that the sitemap is not being cached in a way that serves stale content to Google. Use canonical host settings and consistent delivery paths to minimize scenario-based redirects that can complicate validation and indexing.

External resources you may find valuable include Google's sitemap overview and the official Sitemap Protocol. These resources explain how Google parses sitemaps, common pitfalls, and recommended validation steps. Pairing these external references with in-house checks strengthens your debugging process and demonstrates best-practice adoption in your SEO playbook:

From a workflow perspective, treat sitemap validation as a repeatable process you can apply across multiple properties. The ultimate objective is to maintain a trustworthy sitemap that Google can read reliably, which translates into more consistent indexing signals and faster visibility for newly published pages.

When you’re ready to apply these practices at scale, explore resources in our services or read more practical guides in our blog.

The error message "sitemap could not be read" is more than a technical nuisance; it signals a disconnect between your site and how search engines discover and interpret your structure. When Googlebot or other crawlers encounter a sitemap that they cannot read, they lose a reliable channel to understand which pages exist, when they were updated, and how they are related to one another. For sites like sitemapcouldnotberead.com, this can translate into slower indexing, incomplete coverage, and in some cases, missed opportunities to surface fresh content to users. Recognizing the implications early helps you minimize impact and maintain robust crawl efficiency.

In practical terms, the error creates a black box around your URL dossier. Google relies on sitemaps to cue its crawlers about new or updated content, priority signals, and the overall site taxonomy. When the sitemap is unreadable, the crawl can fall back to discovering URLs through internal links, external links, or direct discovery, which is often slower and less systematic. For SEO teams, that means less predictable crawl coverage, potential delays in indexing new content, and a higher likelihood of important pages remaining undiscovered for longer periods. This is especially consequential for e-commerce catalogs, news publishers, or any site with frequent content updates. To mitigate risk, many sites pair sitemaps with a robust internal linking strategy and ensure that key pages remain easy to find via navigation.

The message can arise from several root causes, all of which share a common theme: the sitemap file cannot be parsed or retrieved in its intended form. Typical triggers include syntax errors in the XML, incorrect encoding, oversized sitemap files, broken or misformatted URLs, access restrictions, and server-side issues that block crawlers. Some errors are temporary, tied to changes in hosting or DNS, while others are persistent until a specific fix is applied. Understanding the nuance of each trigger helps you determine whether a quick patch suffices or a deeper overhaul is required. For reference, Google’s documentation on sitemaps provides guidance on how to structure valid XML and what crawlers expect from a well-formed sitemap. See https://developers.google.com/search/docs/crawl-indexing/sitemaps/overview for details, and align your implementation with official standards.

To validate readability, you can use online XML validators and the crawl-diagnostic tools in Google Search Console. If your site employs a private hosting environment or a CDN, ensure that the sitemap is exposed publicly and that caching policies don’t serve stale or partial content.

For teams operating at scale, a single unreadable sitemap often traces back to a misalignment between file structure and the discovery expectations of crawlers. Large catalogs, rapid product updates, or frequent post revisions can push a sitemap beyond recommended size or update frequency. In such cases, proactive monitoring and modular sitemap design become essential. If you are already consulting our SEO services, you can discuss systemized approaches to sitemap architecture that scale with your site’s growth and update cadence.

Finally, it helps to remember that sitemap readability is not merely about the file itself. It’s also about how accessible the sitemap is to crawlers. Hosting providers, security configurations, and network restrictions can inadvertently shield the file from search engines. Ensure the sitemap URL is correct, public, and delivered with the proper content type, typically application/xml. If you want a quick sanity check, compare the sitemap URL in your robots.txt to confirm there are no disallow rules blocking access. You can review robots.txt best practices and how they interact with sitemaps in credible SEO resources, including guidance from authoritative sources.

By aligning sitemap readability with reliable delivery, you set a foundation for predictable crawl behavior. If you are unsure where to begin, you can explore our contact page for tailored assistance, or review the related sections on our services to understand how sitemap strategy integrates with broader SEO initiatives. For more technical context, consult official documentation and reputable SEO publications referenced above, and keep your internal processes aligned with current best practices in sitemap management.

Sitemaps are not just digital footprints; they are structured guides that help search engines understand your site’s architecture, surface new content quickly, and maintain accurate relationships between pages. For sitemapcouldnotberead.com, grasping the mechanics of how sitemaps work and how Google processes them lays the groundwork for diagnosing unreadable sitemaps more efficiently. This section outlines the core concepts, the typical sitemap formats, and the steps Google takes to read and interpret those files so you can align your implementation with practical, battle-tested practices.

At its essence, a sitemap is an XML document (or a set of them) that enumerates URLs on a site and optionally attaches metadata that signals freshness and importance. For Google and other crawlers, this reduces reliance on chance discovery through internal linking and external references. Instead, the sitemap becomes a deliberate directory that informs the crawler about what exists, what changed, and how pages relate to one another within the site taxonomy. When implemented well, sitemaps accelerate coverage for new or updated content and contribute to a more predictable crawl experience, which is beneficial for sites with dynamic catalogs or frequent publishing cycles.

There are several common sitemap formats, each serving distinct purposes. A standard XML sitemap captures regular pages and their metadata. Other formats include sitemap index files that point to multiple sitemap files, as well as image, video, and news sitemaps designed to cover media and special content types. The right mix depends on site structure, content strategy, and how aggressively you publish updates. For authoritative guidance, Google’s sitemap documentation provides a clear framework for structuring valid XML and leveraging specialized sitemap types when appropriate. See Google's sitemap guidelines for details on layout, encoding, and best practices.

Google begins by fetching the sitemap URL(s) you submit or declare in your robots.txt. Once retrieved, Google parses the XML to extract a sequence of <loc> entries representing actual URLs. Each <loc> is typically accompanied by optional metadata such as <lastmod>, <changefreq>, and <priority>—though Google emphasizes that these metadata signals are hints rather than hard rules. The primary signal Google uses is the URL itself and its accessibility, but the metadata can influence how soon or how often Google considers re-crawling a page. For more technical context, see the official guidance linked above and monitor behavior in Google Search Console’s Crawl reports.

After parsing the sitemap, Google queues eligible URLs for crawling. The crawl budget—the amount of resources Google allocates to a site—must be used efficiently, so maintaining a clean sitemap helps avoid wasted bandwidth on URLs that are duplicates, redirects, or already covered by other discovery signals. In practice, this means ensuring that the sitemap primarily lists canonical, indexable pages that you want crawled and indexed, rather than isolated assets or low-value pages. You can reinforce this by coupling sitemap entries with robust internal linking and a clear site architecture.

It is also important to understand the distinction between discovery and indexing. A sitemap can help Google discover new or updated pages faster, but indexing decisions depend on factors like content quality, page experience signals, canonicalization, and crawlability. When a sitemap is unreadable or inaccessible, Google reroutes its discovery strategy, which may slow indexing and reduce coverage of newly published content. That is why ensuring a readable, accessible sitemap is a foundational SEO practice.

To implement this effectively, you should verify that the sitemap is publicly accessible, served with the correct content type (typically application/xml or application/xml+gzip for compressed files), and updated to reflect the current structure of your site. If you rely on a CDN or caching layer, validate that the sitemap is not served stale content and that the latest version is visible to crawlers. For ongoing optimization, consider registering your sitemap with Google Search Console and periodically reviewing crawl diagnostics to catch anomalies early. When you need strategic help, our team can tailor sitemap-related improvements within broader SEO initiatives. Visit our services to learn more, or contact us for direct assistance.

In practice, the most effective sitemap strategies balance breadth and precision. A comprehensive sitemap that remains well-formed and updated, paired with a clean internal linking structure and a robust robots.txt configuration, creates a reliable pathway for crawlers to discover and index your content. This alignment reduces the risk of unreadable sitemaps causing gaps in indexing and helps maintain healthy crawl activity over time.

Unreadable sitemaps almost always trace back to a handful of practical issues. By cataloging the most frequent culprits, SEO teams can establish a repeatable diagnostic workflow that reduces downtime and preserves crawl coverage. This section focuses on the root causes, with concrete steps you can take to verify and remediate each one. For teams working on our services, these checks fit neatly into a broader sitemap optimization plan that complements ongoing technical SEO efforts for direct assistance.

Below, you’ll find the most frequent failure modes, organized for quick diagnosis. For each cause, start with a minimal validation pass, then escalate to targeted fixes that align with your site architecture and publishing cadence.

XML syntax problems are the most common trigger for a sitemap that cannot be read. Even a small syntax error—such as an unclosed tag, a misspelled element, or illegal characters in <loc> entries—can render the entire file invalid for parsing. Encoding mistakes, especially when non-ASCII characters appear in URLs or date stamps, can also break parsing rules for crawlers. In practice, these issues often originate from automated generation processes that do not strictly enforce XML well-formedness at scale.

What to check and how to fix:

<urlset> element with valid <url> entries.Tip: use Google’s official sitemap guidelines as a reference point for structure, encoding, and validation practices. Consider consolidating the validation workflow into a CI step so every sitemap rebuild is checked before deployment. If you need practical guidance tailored to your platform, our team can help map validation rules to your deployment pipeline.

For broader context on typical sitemap formats and how they’re interpreted by search engines, see external references such as Moz’s overview of sitemaps. Moz: What is a Sitemap.

Encoding mistakes often surface when URLs include non-ASCII characters or when lastmod timestamps use nonstandard formats. Also, missing schemes (http or https) or spaces in URLs can break parsing. Search engines expect precise, well-formed URLs and consistent timestamp formats. Even minor deviations can cascade into read failures.

Key remediation steps include:

If your sitemap lives behind a content delivery network or a security layer, verify that the encoding and content-type headers remain stable across cache refresh cycles. A mismatched header or stale cache can masquerade as a read failure even when the XML is technically valid. When you need a robust, repeatable encoding policy, our team can assist with implementation and validation aligned to your CMS or hosting environment.

Alongside practical checks, consider extending your sitemap approach with a sitemap index that references multiple smaller sitemaps. This reduces risk from large files and makes validation responsibilities more manageable. If you want to explore how to architect a scalable sitemap strategy, see our services or reach out via the contact page.

Large sitemaps are not inherently unreadable, but they become fragile when they approach platform limits or when they mix content types in ways that complicate parsing. Oversized files increase the surface area for errors and slow down validation cycles. Duplicates and inconsistent scope—listing the same URL under multiple entries or including non-indexable assets—dilute crawl efficiency and can cause confusion for crawlers trying to prioritize indexing.

Actions to mitigate these risks:

For large catalogs, this approach improves crawl efficiency and reduces the likelihood that readers encounter unreadable or partially loaded files. If you’re unsure how to segment your sitemap effectively, we can tailor a modular strategy that fits your site’s architecture and update cadence.

Access controls that block crawlers or misconfigure HTTP responses are frequent culprits in read failures. A sitemap that returns 403 or 401, or one that is behind a login or IP restriction, will not be readable by Googlebot or other crawlers. Similarly, intermittent 5xx server errors or timeouts prevent reliable retrieval, triggering crawl issues and stalled indexing.

Practical steps to address access problems include:

If you operate behind a firewall or OAuth-protected environment, consider offering a read-only public exposure for the sitemap to avoid crawl blocking. For ongoing assurance, configure automated health checks that alert you when the sitemap becomes temporarily unavailable or starts returning non-200 responses.

When you encounter a read failure caused by access or delivery issues, pair quick recoveries with a longer-term plan. Document the root cause, implement a targeted fix, and re-run validation to confirm successful read-by-crawlers before re-submitting to Google Search Console or other tooling. If you need a structured diagnostic workflow, our team can help design and implement it, ensuring that fixes are reproducible and tracked across deployments.

How to proceed next depends on your current setup. If you’re managing sitemaps manually, start with a thorough XML validation and a review of your hosting and caching layers. If you’re using an automated generator, integrate these checks into your CI/CD pipeline and consider splitting large files as a standard practice. For organizations seeking steady improvements, we offer tailored sitemap engineering as part of broader SEO optimization services. Explore our services or contact us for a targeted engagement that aligns with your publishing cadence and technical constraints.

This completes a focused look at the most common causes of sitemap read failures. In the next section, you’ll find guidance on interpreting error messages across tooling and how to translate those signals into concrete fixes that restore crawl coverage promptly.

When crawlers report read failures, the message is only the first clue. Interpreting the exact error signal within diagnostic tools is essential to map to concrete fixes. This part explains how to translate common messages into actionable steps that restore crawl coverage for sitemap could not be read issues.

Key tool surfaces include Google Search Console, the Sitemaps report, Crawl Stats, and live fetch diagnostics. Other platforms like Bing Webmaster Tools or your hosting provider dashboards can reveal complementary signals such as DNS problems or 5xx errors that block retrieval. Collecting these signals together helps you identify whether the root cause sits in the sitemap file, the hosting environment, or the delivery network.

To structure your triage, start with the most actionable observations: is the sitemap itself readable via a direct URL? Do you receive an HTTP 200 for the sitemap fetch? If the tool reports an XML parsing error, locate the line or entry with the culprit. If the tool reports a status like 403 or 401, focus on access permissions. If the messages indicate a DNS resolution failure, you know the issue is at the domain level rather than the file format.

For teams using Google Search Console, the Crawl and Sitemaps reports often provide a direct path from the error message to the affected sitemap URL and the exact line in the sitemap where the problem occurs. This direct mapping accelerates the fix cycle and reduces guesswork. If you need a guided assessment, you can review our services or contact us for a targeted diagnostic engagement tailored to sitemap reliability.

In addition to signal interpretation, maintain a running log of issues, fixes applied, and outcomes observed in subsequent crawls. This practice creates a feedback loop that improves both the tooling signals you rely on and the stability of your sitemap delivery. If you want hands-on help implementing a repeatable diagnostic protocol, explore our SEO services or reach out via the contact page.

Finally, as you integrate interpretive rigor into your workflow, align your conclusions with a broader sitemap maintenance plan. Clear ownership, defined SLOs for uptime of the sitemap URL, and automated checks reduce the risk of reintroducing unreadable sitemaps after deployment. For a scalable approach, consider our sitemap-focused services described on the /services/ page or contact us to schedule a tailored session.

A sitemap is a structured map of a website’s pages, designed to help search engines discover and understand content. For most sites, it serves as a navigational aid that communicates the breadth and depth of available URLs, their last modification dates, and how pages relate to one another. There are two common forms: an XML sitemap, which lists individual pages, and a sitemap index, which points to multiple sitemap files. When a site such as sitemapcouldnotberead.com relies on these files for crawl guidance, any disruption in access can slow or stall indexing. A failed read, often expressed as sitemap could not be read or couldn t fetch, signals more than a single server hiccup; it can indicate broader configuration or access issues that affect how search engines discover content. For stakeholders, recognizing the impact early helps preserve crawl efficiency and preserve existing rankings.

Guidance from authoritative sources emphasizes that sitemaps are especially valuable for large sites, sites with rapidly changing content, or sections that are hard to reach through internal linking alone. They are not a replacement for good internal linking, but they augment discovery when bots cannot easily find pages through the site’s navigation. For practitioners at sitemapcouldnotberead.com, this distinction translates into practical steps: ensure the sitemap is timely, complete, and reachable, while maintaining healthy crawlability across the entire domain.

From a strategic perspective, a functioning sitemap helps allocate crawl budget efficiently. When search engines encounter a readable sitemap, they gain explicit signals about updated content, priority, and frequency. If the sitemap cannot be read, the onus falls back to the site’s internal linking structure and external references for discovery. This is why early detection and remediation are critical for preserving indexing momentum, especially for new domains or sites with a large catalog of pages. For deeper reference on sitemap best practices, see Google's sitemap overview and guidelines from other major search engines.

In practice, the read fetch issue can appear in various forms: a sitemap that never loads, a file that returns errors, or a response that is blocked by server policies. Recognizing these symptoms is the first step toward a reliable remediation path. This part of the guide sets the stage for a systematic approach to diagnosing and fixing read fetch failures, so you can restore smooth crawling and indexing. To support ongoing maintenance, consider pairing sitemap monitoring with proactive checks of robots.txt, server access controls, and DNS health. This holistic view reduces the risk that a single fault blocks visibility for a large portion of the site.

If you are exploring related services or want a structured approach to SEO health, you may review our SEO Audit Service for a comprehensive crawl and indexability assessment. It complements the sitemap-focused guidance by validating internal linking, canonicalization, and site-wide accessibility across layers that influence how search engines crawl and index content.

In the sections that follow, we break down the read fetch scenario into actionable steps. You will learn how to verify URL accessibility, interpret HTTP responses, and distinguish between issues at the DNS, hosting, or network levels versus problems rooted in the sitemap file itself. The goal is to equip you with a repeatable diagnostic mindset that can be applied to any site facing a sitemap could not be read or couldn t fetch scenario.

Beyond technical fixes, sustaining sitemap health requires ongoing governance. Regularly validating the sitemap's structure, ensuring it remains within size limits, and keeping the sitemap index up to date with newly discovered URLs are essential practices. Building a monitoring routine that flags read fetch failures as soon as they appear helps maintain momentum in indexing and prevents gradual degradation of visibility. For authoritative guidance on sitemap integrity and schema, consult standard references in the field, and integrate insights into your internal playbooks.

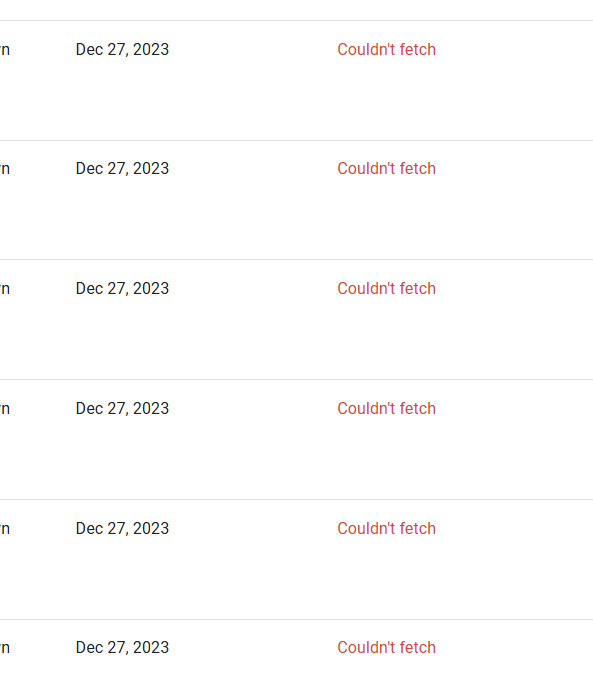

When a sitemap cannot be read or fetched, several signals surface across diagnostic tools and server logs. Early recognition helps contain crawl disruption and preserve indexing momentum for a site like sitemapcouldnotberead.com. Identifying these symptoms quickly allows teams to distinguish between transient network blips and deeper configuration issues that block discovery of content.

One of the most immediate signs is a direct fetch error on the sitemap URL. If a search engine or a crawler attempts to retrieve sitemap.xml and receives a 404, 403, or a redirect to an error page, the sitemap cannot guide crawling and indexing for the pages it lists. This disrupts the explicit signals that help search engines prioritize updated content.

These symptoms warrant a targeted triage to distinguish between network, hosting, and content-level issues. In many cases, a quick check of the exact HTTP status, the agent used by the crawler, and the response headers clarifies where the fault lies. If the sitemap is served via a content delivery network (CDN) or gzip-compressed file, verify that the correct Content-Encoding header is applied and that crawlers can decompress the payload.

To guide remediation, rely on concrete steps rather than assumptions. A measurable signal is the combination of a failing fetch and a non-200 response from the sitemap URL, coupled with a corresponding log entry on the hosting stack. For more systematic guidance on sitemap health and indexability, you may review our SEO Audit Service for a comprehensive crawl and indexability assessment.

In practice, many read/fetch failures show up in batches rather than as isolated incidents. A temporally clustered set of errors often points to a recent deployment, a CDN edge node misconfiguration, or a temporary hosting outage. Maintaining a consistent diagnostic cadence helps ensure you don’t miss gradual degradation that affects crawl efficiency over weeks, not days.

A 404 status on the sitemap URL often signals that the file was moved, renamed, or was never deployed to the expected path. Confirm the exact location of the sitemap (for example, at the root or within a subdirectory) and verify that the web server hosts the file under that path. If you use a canonical domain or a preproduction environment, ensure the production URL is the one submitted to search engines.

403 responses typically indicate permission problems, such as restrictive .htaccess rules, an IP allowlist that doesn’t include search engine bots, or misconfigured sitemaps behind authentication. Review file permissions, directory traversal rules, and any security modules that might inadvertently shield the sitemap from legitimate crawlers.

Server-side failures can arise from temporary outages, resource limits during peak traffic, or misbehaving modules. Check server load, error logs, and any recent deployments that could destabilize the response path to the sitemap file. A brief maintenance window should be reflected in DNS and CDN health, with a plan to re-test once stability returns.

Malformed XML, incorrect encoding, or violations of the Sitemap XML schema prevent crawlers from parsing the file, even if it is served correctly. Validate the sitemap with an XML schema validator and confirm that special characters, CDATA blocks, and URL encoding comply with the standard sitemap protocol. If you use a sitemap index, ensure each referenced sitemap is valid and accessible.

Large sitemaps approaching the 50MB limit or more than 50,000 URL entries introduce the risk of partial loading or timeouts. When using a sitemap index, ensure all referenced sitemaps are reachable and properly linked. Review any automated sitemap generators to confirm they respect the size and URL constraints of the target search engines.

Because the sitemap serves as a discovery bridge, any reliability issue translates into reduced crawl velocity and potential skip of new or updated pages. The moment you observe any of the symptoms above, capture the exact URL, the status code, the date, and the user agent, then proceed with a controlled verification across multiple networks to determine if the problem is regional or global.

Ongoing monitoring is essential. A lightweight monitoring routine that checks the sitemap at regular intervals, complemented by robots.txt audits and DNS health checks, forms the baseline for sustainable sitemap health. If you want a structured, repeatable process, our team documents a diagnostic workflow in our SEO playbooks to help maintain a healthy crawl footprint across evolving site structures.

Regular health checks also support rapid detection of changes in hosting or network configurations. Coordinating with the hosting provider and CDN operator can reduce resolution time and minimize crawl disruption. For sites like sitemapcouldnotberead.com, a disciplined approach to symptoms translates into a resilient crawl strategy that sustains visibility even when technical hiccups occur.

Even when a sitemap file exists on the server, its usefulness depends on being accessible to crawlers. In most read/fetch failures, the root causes fall into three broad categories: server configuration, access controls, and the accuracy of the sitemap URL itself. Understanding how these areas interact helps prioritize fixes and prevents repeat incidents for a site like sitemapcouldnotberead.com.

To begin triage, map the problem to one of these three buckets. Each bucket has specific signals, easy verification steps, and common fixes that minimize downtime and preserve crawl momentum.

Recognizing where the fault lies informs the remediation plan. For example, a 404 on sitemap.xml that persists across multiple agents typically signals a path misalignment, whereas a 403 response often points to permission rules or IP blocks. If you need a guided, end-to-end diagnostic framework, our SEO Audit Service provides a structured crawl and indexability assessment designed to catch these core issues quickly.

The web server configuration determines how static files such as sitemap.xml are located and delivered. Common trouble spots include an incorrect document root, misconfigured virtual hosts, or rewrite rules that accidentally shield the sitemap from crawlers. Check for the following specifics: the sitemap is placed under the public document root, the file path matches what is published in robots or sitemap indexes, and that the server returns a 200 OK for requests from search engine user agents. For sites relying on CDNs, ensure the origin response is consistent and that edge rules do not strip the sitemap or serve a compressed payload with improper headers.

Review server logs around the time of fetch attempts to identify 4xx or 5xx errors, which indicate permission issues or temporary outages. Validate content-type delivery (ideally application/xml or text/xml) and confirm there are no unexpected redirects that would strip query strings or alter the URL used by the crawler. If you are unsure, perform a direct fetch using a tool like curl from different networks to confirm a consistent response across environments.

Access controls, including IP allowlists, firewalls, and web application firewalls (WAFs), can inadvertently block legitimate crawlers. When a sitemap fetch fails due to access rules, you may observe 403 errors, rate limiting, or bursts of blocked requests in logs. Practical checks include: verifying that search engine IPs and user-agents are permitted, inspecting any authentication requirements for the sitemap path, and reviewing security module logs for blocked requests linked to the sitemap URL.

Ensure that the sitemap is publicly accessible without authentication, unless you have a deliberate strategy to expose it via a controlled mechanism. If a WAF is in place, create an exception for sitemap.xml or for the sitemap path, and periodically review rules to avoid accidental blocks caused by criteria that are too broad. After changes, re-test by requesting the sitemap URL directly and via the crawler user-agent to confirm resolution.

The final category focuses on the URL itself. Linux-based hosting treats paths as case sensitive, so sitemap.xml at /sitemap.xml may differ from /Sitemap.xml. Likewise, the coexistence of http and https, www and non-www variants, and trailing slashes can create gaps between what is submitted to search engines and what actually exists on the server. Key checks include: ensuring the sitemap URL matches the exact path used by your server, confirming consistency across canonical domain settings, and validating that the sitemap index references valid, reachable sitemaps with correct relative paths.

Another frequent pitfall is misalignment between the sitemap’s declared URLs and the domain search engines crawl. If you publish a sitemap at https://example.com/sitemap.xml but robots.txt or the sitemap index references pages on http://example.org, crawlers will fail to map content correctly. Ensure the destination domain, protocol, and path are uniform across your sitemap, robots.txt, and submitted feed. For ongoing optimization, consider maintaining a simple mapping check as part of your weekly health routine, and consult our SEO Audit Service for rigorous checks on crawlability and indexability.

When a sitemap cannot be read or fetched, the first practical step is to verify the sitemap URL itself and the HTTP response it yields. This verification not only confirms the presence of the file but also uncovers whether the issue lies with the hosting environment, network path, or the sitemap content. For a site like sitemapcouldnotberead.com, a disciplined, manual verification process helps isolate transient glitches from systemic misconfigurations, enabling targeted remediation without unnecessary guesswork.

Begin with a direct check from multiple access points: a browser, a command line tool, and, if possible, a test from a different geographic region. This multidimensional check helps determine if the problem is regional or global and if it affects all crawlers equally or only specific user agents. The goal is to observe the exact HTTP status code, any redirects, and the final destination that a crawler would reach when requesting the sitemap.

For practical commands you can start with, use a browser-inspection tool or a curl-based approach. For example, a simple status check can be done by requesting the sitemap and observing the first line of the response headers. If curl is available, you can run: curl -I https://sitemapcouldnotberead.com/sitemap.xml. If a redirect is involved, follow it with curl -I -L https://sitemapcouldnotberead.com/sitemap.xml to see the final destination and the status at each hop. These actions clarify whether the problem is a 404, a 403, or a more nuanced redirect chain that fails to deliver the content to crawlers.

Beyond initial status codes, pay close attention to response headers. Key indicators include Content-Type, Content-Length, Cache-Control, and Content-Encoding. A mismatch in Content-Type (for example, text/html instead of application/xml) can cause crawlers to misinterpret the payload, even if the file is technically reachable. Content-Encoding reveals whether the sitemap is compressed (gzip, deflate) and whether the crawler can decompress it on the fly. If a sitemap is gzip-compressed, ensure the server advertises Content-Encoding: gzip and that the final, decompressed content remains valid XML.

One common pitfall is the subtle effect of redirects on crawlers. If a sitemap URL redirects to a page that requires authentication or to a page with a different canonical domain, search engines may abandon the fetch path. In such cases, conducting a redirect audit—documenting the exact chain and the HTTP status of each hop—helps determine whether the sitemap path is still a reliable entry point for crawl discovery.

In addition to direct checks, validate that the sitemap is accessible to common search engine bots by simulating their user agents in curl: curl -A 'Googlebot/2.1 (+http://www.google.com/bot.html)' -I https://sitemapcouldnotberead.com/sitemap.xml. Discrepancies between browser results and crawler simulations often signal access controls or firewall rules that treat bots differently than human users. If such discrepancies appear, review server access controls, IP allowlists, and security modules that could selectively block automated agents.

When access is restricted by a firewall or WAF, temporary whitelisting of the crawler IP ranges or user-agents can restore visibility while keeping security intact. After any change, re-run the same verification steps to confirm that the sitemap is consistently retrievable under both normal and crawler-like conditions. If you need a repeatable workflow to maintain this level of assurance, our SEO Audit Service provides a structured crawl and indexability assessment that incorporates sitemap reachability checks alongside broader site health indicators.

In cases where the sitemap is served through a content delivery network (CDN) or edge caching layer, replicate the checks at both the origin and the edge. A successful fetch from the origin but not from the edge indicates propagation delays, stale caches, or edge-specific rules that may require purging caches or updating edge configurations. Document the results across layers to pinpoint precisely where the barrier originates.

Finally, if the sitemap uses an index file to reference multiple sub-sitemaps, validate each referenced sitemap individually. A single inaccessible sub-sitemap breaks the integrity of the entire index and can prevent search engines from indexing a portion of the site even if other entries are healthy. The remediation path may involve regenerating the affected sub-sitemaps, correcting URL paths, or adjusting the index structure to reflect the actual site architecture.

As you complete this verification cycle, maintain a record of all observed results, including the exact URL, status codes, timestamps, and the agents used. This creates a traceable diagnostic trail that supports faster remediation and helps prevent recurrence. If you observe recurring patterns across multiple pages or domains, consider expanding the scope to include DNS health, hosting stability, and network-level routing—a holistic view that reinforces the reliability of your sitemap as a tool for efficient crawl and indexing.

For ongoing improvements and to ensure consistent visibility, you can complement this protocol with a formal sitemap health checklist and periodic audits. The goal is to preserve crawl efficiency and ensure timely indexing, even when infrastructure changes occur. If you want a rigorous, repeatable process for sitemap health, explore our SEO playbooks and services, including the SEO Audit Service mentioned above.

The message Shopify sitemap could not be read signals a disruption in how search engines discover and index a storefront’s pages. A sitemap is the map that helps crawlers understand the breadth and structure of your site. When that map is unreadable, search engines lose visibility into new products, collections, blog posts, and critical informational pages. For Shopify stores, where product feeds change frequently and timing matters for ranking and traffic, a readable sitemap is a core technical signal that supports rapid indexing and accurate representation in search results.

In practical terms, this error can slow or prevent the indexing of newly added products, price updates, and content revisions. The result is delayed visibility in search results, missed opportunities for organic traffic, and potential confusion for customers who rely on organic search to discover items that are in stock or on sale. From an ecommerce perspective, even a short window without readable sitemaps can translate into incremental drops in impressions and clicks, especially during product launches, promotions, or seasonal campaigns.

Shopify’s sitemap ecosystem is designed to be robust while remaining simple for store owners and developers. Shopify generates a core sitemap at the conventional location /sitemap.xml and many ecommerce sites rely on a hierarchy of sub-sitemaps that cover products, collections, blogs, and informational pages. When the sitemap cannot be read, that entire chain of signals is disrupted. The impact is not just about pages appearing in search; it also affects how search engines assess crawl frequency, canonical relationships, and freshness signals for category pages and blog entries.

For readers planning troubleshooting in stages, this article begins with the core concepts and then moves into practical diagnosis and fixes in subsequent parts. If you are evaluating the issue as part of a broader SEO audit, consider correlating sitemap readability with recent site changes, server performance, and how your Shopify theme interacts with URL generation and redirects. A readable sitemap complements other technical health checks, such as ensuring proper robots.txt directives and valid SSL, to maintain a healthy crawl budget and accurate indexing for a Shopify storefront.

Internal resources can help you navigate this concern. For a guided overview of how we approach Shopify sitemap audits and optimization, visit our Services page. External references from industry authorities provide additional context on sitemap best practices and validation practices, including Google’s guidance on sitemap structure and submission workflows. These sources reinforce the importance of readable sitemaps as a foundational SEO signal for ecommerce sites.

Understanding the baseline expectation is crucial. When the sitemap is readable, search engines can quickly parse the list of URLs, detect priority changes, and reprocess updates with minimal delay. When readability fails, the system behaves as if pages exist but are invisible to crawlers, which can lead to stale SERP listings and missed opportunities for visibility on high-intent queries.

From a strategic standpoint, this issue deserves prompt attention. It affects not only the technical health of the site but also the trust and reliability of the storefront in the eyes of both customers and search engines. A clear, accessible sitemap signals to all parties that the store is well-maintained, up-to-date, and capable of delivering a consistent user experience. That alignment is particularly important for Shopify merchants competing in crowded markets where crawl efficiency and rapid indexing can influence share of voice.

In the following sections, we progressively break down how sitemaps work conceptually, the typical structure for storefronts, common error signals to watch for, and practical steps to diagnose and repair issues. Each part builds on the previous one to create a practical, actionable roadmap you can apply to Shopify stores facing sitemap readability problems.

For a quick diagnostic reference, consider starting with a basic check of your sitemap URL in the browser or a curl request to confirm HTTP status. A healthy sitemap should respond with a 200 OK and deliver valid XML. If you see 4xx or 5xx errors, or a response that isn’t XML, you’re looking at the core symptoms of unreadability. The next steps will guide you through identifying the root cause and applying targeted fixes.

As you progress through this article, you’ll encounter concrete checks, validation steps, and recommended practices aligned with industry standards. The goal is to restore readable, crawlable sitemaps that enable Shopify stores to compete effectively in the organic search landscape.

Key external references you may consult include Google’s guidelines on building and submitting a sitemap and industry resources that detail validation practices for XML sitemaps. These sources provide authoritative context on protocol rules, encoding, and common pitfalls. By aligning with these standards, you reinforce the technical foundation that underpins strong SEO performance for Shopify stores.

When the sitemap is unreadable, the immediate consequence is a gap in how content is discovered and indexed. New products may not appear in search results promptly, which is particularly impactful during promotions or restocks. Category pages that rely on dynamic URL generation can also lag in representation if the sitemap cannot be parsed correctly. Even if the homepage and critical pages are accessible, the broader catalog sections may remain underindexed, reducing overall organic visibility and traffic potential.

From a user experience perspective, the timing of updates matters. If a price change, inventory adjustment, or new collection relies on sitemap-driven indexing, a delay in discovery translates into customer friction—items appearing as unavailable or out of stock in search results. That friction can push prospective buyers toward competitors, especially in fast-moving product categories. Addressing sitemap readability is thus not only a technical task but a business efficiency measure that supports revenue continuity.